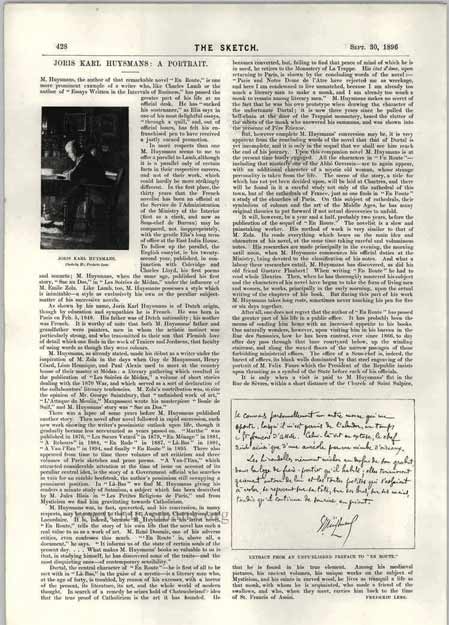

JORIS KARL HUYSMANS: A PORTRAIT

M. Huysmans, the author of that remarkable novel "En Route," is one more prominent example of a writer who, like Charles Lamb or the author of "Essays Written in the Intervals of Business," has passed the greater part of his life at an official desk. He has "sucked his sustenance," as Elia says in one of his most delightful essays, "through a quill," and, out of official hours, has felt his enfranchised pen to have received a justly earned promotion.

In more respects than one M. Huysmans seems to me to offer a parallel to Lamb, although it is a parallel only of certain facts in their respective careers, and not of their work, which could hardly be more strikingly different. In the first place, the thirty years that the French novelist has been an official at the Service de l’Administration of the Ministry of the Interior (first as a clerk, and now as Sous-chef de Bureau) may be compared, not inappropriately, with the gentle Elia’s long term of office at the East India House. To follow up the parallel, the English essayist, in his twenty-second year, published, in conjunction with Coleridge and Charles Lloyd, his first poems and sonnets; M. Huysmans, when the same age, published his first story, "Sac au Dos," in "Les Soirées de Médan," under the influence of M. Emile Zola. Like Lamb, too, M. Huysmans possesses a style which is inimitable — a style as exclusively his own as the peculiar subject-matter of his successive novels.

As shown by his name, Joris Karl Huysmans is of Dutch origin, though by education and sympathies he is French. He was born in Paris on Feb. 5, 1848. His father was of Dutch nationality; his mother was French. It is worthy of note that both M. Huysmans’ father and grandfather were painters, men in whom the artistic instinct was particularly strong, and who transmitted to their son that Flemish love of detail which one finds in the work of Teniers and Jordaens, that faculty of using words as though they were colours.

M. Huysmans, as already stated, made his début as a writer under the inspiration of M. Zola in the days when Guy de Maupassant, Henry Céard, Léon Hennique, and Paul Alexis used to meet at the country house of their master at Médan: a literary gathering which resuIted in the publication of "Les Soirées de Médan," a volume of short stories dealing with the 1870 War, and which served as a sort of declaration of the collaborators’ literary tendencies. M. Zola’s contribution was, to cite the opinion of Mr. George Saintsbury, that "unfinished work of art" "L’Attaque du Moulin," Maupassant wrote his masterpiece "Boule de Suif," and M. Huysmans’ story was " Sac au Dos."

There was a lapse of some years before M. Huysmans published another story. Then novel after novel followed in rapid succession, each new work showing the writer’s pessimistic outlook upon life, though it gradually became less accentuated as years passed on. "Marthe" was published in 1876, "Les Soeurs Vatard" in 1879, "En Ménage’’ in 1881, "A Rebours’’ in 1884, "En Rade" in 1887, "Là-Bas’’ in 1891, "A Vau-l’Eau" in 1894, and finally "En Route" in 1895. There also appeared from time to time three volumes of art criticism and three volumes of Paris sketches and prose poems. "A Vau-l’Eau,’’ which attracted considerable attention at the time of issue on account of its peculiar central idea, is the story of a Government official who searches in vain for an eatable beefsteak, the author’s pessimism still occupying a prominent position. In "Là-Bas’’ we find M. Huysmans giving his readers a minute study of Satanism, a subject which has been described by M. Jules Bois in "Les Petites Religions de Paris,’’ and from Mysticism we find him gravitating towards Catholicism.

M. Huysmans was, in fact, converted, and his conversion, in many respects, may be compared to that of St. Augustine. Chateaubriand, and Lacordaire. It is, indeed, because M. Huysmans in his latest novel, "En Route," tells the story of his own life that the novel has such a real value to us as a work of art. M. René Doumic, one of his adverse critics, even confesses this much. "En Route" is, above all, a document," he says. "It informs us of the state of certain souls of the present day... What makes M. Huysmans’ books so valuable to us is that, in studying himself, he has discovered some of the traits — and the most disquieting ones — of contemporary sensibility."

Durtal, the central character of "En Route" — he is first of all to be met with in "Là-Bas," in the guise of a mystic — is a literary man who, at the age of forty, is troubled, by reason of his excesses, with a horror of the present, its literature, its art, and the whole world of modern thought. In search of a remedy lie seizes hold of Chateaubriand’s idea that the true proof of Catholicism is the art it has founded. He becomes converted, but, failing to find that peace of mind of which he is in need, he retires to the Monastery of La Trappe. His état d’âme, upon returning to Paris, is shown by the concluding words of the novel: — "Paris and Notre Dame do l’Atre have rejected me as wreckage, and here I am condemned to live unmatched, because I am already too much a literary man to make a monk, and I am already too much a monk to remain among literary men." M. Huysmans makes no secret of the fact that he was his own prototype when drawing the character of the unfortunate Durtal; it is now three years since he pulled the bell-chain at the door of the Trappist monastery, heard the clatter of the sabots of the monk who answered his summons, and was shown into the presence of Père Etienne.

But, however complete M. Huysmans’ conversion may be, it is very apparent from the concluding words of the novel that that of Durtal is yet incomplete, and it is only in the sequel that we shall see him reach the end of his journey. Upon this companion novel M. Huysmans is at the present time busily engaged. All the characters in "En Route" — including that masterly one of the Abbé Gevresin — are to again appear, with an additional character of a mystic old woman, whose strange personality is taken from the life. The scene of the story, a title for which has not yet been decided upon, will be laid at Chartres, and there will be found in it a careful study not only of the cathedral of this town, but of the cathedrals of France, just as one finds in "En Route" a study of the churches of Paris. On this subject of cathedrals, their symbolism of colours and the art of the Middle Ages, he has many original theories to put forward if not actual discoveries to unfold.

It will, however, be a year amid a half, probably two years, before the publication of the sequel of "En Route." The novelist is a slow and painstaking worker. His method of work is very similar to that of M. Zola. He reads everything which bears on the main idea and characters of his novel, at the same time taking careful and voluminous notes. His researches are made principally in the evening, the morning until noon, when M. Huysmans commences his official duties at the Ministry, being devoted to the classification of his notes. And what a labour these researches entail. M. Huysmans has discovered, as did his old friend Gustave Flaubert! When writing ’’En Route’’ he had to read whole libraries. Then, when he has thoroughly mastered his subject and the characters of his novel have begun to take the form of living men and women, he works, principally in the early morning, upon the actual writing of the chapters of his book. But during this part of his work M. Huysmans takes long rests, sometimes never touching his pen for five or six days together.

After all, one does not regret that the author of "En Route" has passed the greater part of his life in a public office. It has probably been the means of sending him home with an increased appetite to his books. One naturally wonders, however, upon visiting him in his bureau in the Rue des Saussaies, how he has been content, ever since 1866, to day after day pass through that bare courtyard below, up the winding staircase, and along the waxed floors of the narrow passages of those forbidding ministerial offices. The office of a Sous-chef is, indeed, the barest of offices, its blank walls dominated by that steel engraving of the portrait of M. Felix Faure which the President of the Republic insists upon thrusting as a symbol of the State before each of his officials.

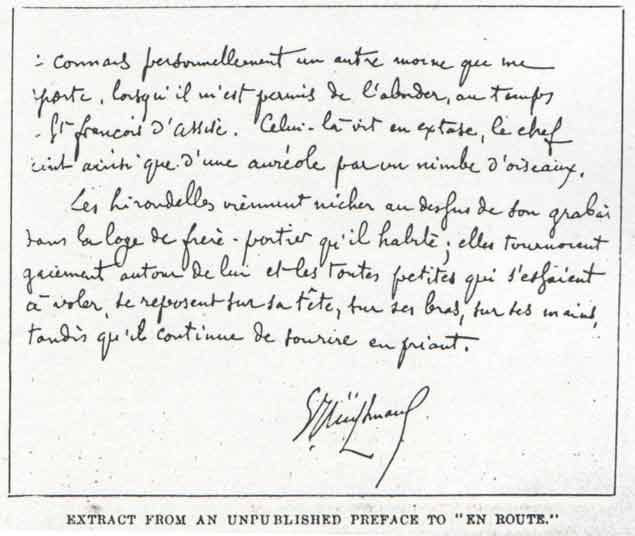

It is only when a visit is paid to M. Huysmans’ flat in the Rue de Sèvres, within a short distance of the Church of Saint Sulpice, that he is found in his true element. Among his mediaeval pictures, his ancient volumes, his unique works on the subject of Mysticism, and his saints in carved wood, he lives as tranquil a life as that monk, with whom he is acquainted. who made a friend of the swallows, and who, when they meet, carries him back to the time of St. Francis of Assisi.

FREDERIC LEES.