An ‘unpublished’ letter from J-K Huysmans to Myriam Harry.

Brendan King

In 1932 Myriam Harry published a volume of literary memoirs, Trois ombres, which, alongside her reminiscences of Jules Lemaître and Anatole France, purported to include a frank and detailed account of her friendship with J.-K. Huysmans during his final years. The memoir contained a number of dramatic disclosures which have subsequently come to be relied on by so many of Huysmans’ biographers that they have become an established part of the Huysmans’ myth. Anyone who has read Robert Baldick’s life, for example, will be familiar with the broad outline of the story: after Huysmans initially mistakes Harry for a male writer, a tentative introduction between the literary lion and the young tyro leads to a deep friendship between the two, and in a series of frank tête-à-têtes, Harry’s feminine charm elicits the kind of personal admissions from the older writer — thoughts of suicide, tearful regrets over past love affairs and so on — that he confided to few if any of his more long-standing male friends and colleagues.

A few examples from biographies and studies published since 1932 will suffice to show how some of these claims have been elevated to the status of accepted fact, through mere repetition. Harry’s recollection that, during an intimate talk, Huysmans had broken down in tears and confided that he had wasted his life is repeated by H. M. Gallot (1954),Robert Baldick (1955), Guy Chastel (1957), Paul Leautaud (1968), and Fernande Zayed (1973), among others. Harry's claim that Huysmans considered suicide while living at the rue Monsieur is repeated by Georges Veysset (1950), Robert Baldick (1955), Christopher Lloyd (1975), and Patrice Locmant (2007). Whether one is writing history or biography, no single source should ever be unequivocally relied on, yet again and again in biographical accounts of Huysmans’ life it turns out that the sole source for Harry’s striking claims and assertions turns out to be Harry herself.

Unfortunately, there are strong reasons for doubting Harry’s testimony. Indeed, one could go further. The evidence proves conclusively that Harry not only fabricated stories to pad out her recollections of Huysmans, which were constantly re-edited and repackaged over the course of more than 40 years in the wake of the older writer's death, she also deliberately altered the documents she published to make her relationship seem of longer standing than it actually was.

In order to show the extent of Harry’s misinformation and manipulation I intend in this essay to rely only on contemporary sources and authentic documents for which the originals are known to exist, rather than on unsupported assertions. The most obvious place to look for supporting documentary evidence about the friendship between Harry and Huysmans is in the letters that the two writers exchanged. This would not only provide a superstructure of dates and other factual references, but would also give a sense of the level of intimacy between the two correspondents. However, for a number of reasons this first line of research is not as fruitful as one might have hoped. The Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, though it is furnished with the originals of a significant portion of Huysmans’ correspondence, actually holds no originals of letters from Huysmans to Harry. The library catalogue refers to the letters, but the microfilm contains only a typed transcript of those that Harry herself had reproduced in her various memoirs. The transcript of these letters has been annotated by Lucien Descaves and it is clear that he had his own doubts about Harry’s integrity as a witness. His notes point out a number of discrepancies between the different printed versions, effectively a catalogue of variations, omissions and additions that Harry inflicted on the letters for dramatic or narrative effect. Noting, for example, that the same letter had been printed with different dates in two different publications, Descaves resigns himself to the laconic observation that ‘les deux dates me paraîssent douteux, l’une et l’autre’.(1)

The problem for Descaves was that he did not have the originals to hand in order to compare them with the published versions. Logically, the next place to look for the originals of Huysmans’ letters to Harry, if they still exist, is in Harry’s own literary archive. However, this approach also leads to an impasse. Harry’s archive was previously in the possession of her adoptive son, Faouaz (François) Perrault-Harry,(2) and he consistently denied researchers access to it. Although he has since died and the archives – or what remains of them at least – were auctioned in Paris in 2019, they seem to have included no documents that would prove Harry’s version of events. Harry’s most recent biographer, Cécile Chomabard-Gaudin, strongly suspected that Harry had been somewhat economical with the truth and had, at the very least, ‘arranged’ her memoirs, but having been denied access to the material in Harry’s archive she found it difficult to obtain any hard documentary proof.(3)

However, a letter from Huysmans to Harry has recently come to light, and a comparison with the version of the same letter as it appears in Trois ombres reveals that the history of the friendship between the two writers needs to be rewritten. It is probably useful here to reprint Huysmans’ letter that Harry published in both the 1908 and 1932 versions of her memoirs. The letter clearly marks a significant point in their relationship, with the older novelist inviting the supposedly young male writer to visit him whenever he likes:

60 rue de Babylone.

Paris, le 4 décembre 1902

Mon cher confrère,

Je suis tout à votre disposition pour vous aider à trouver, si je le puis, les renseignements dont vouz avez besoin pour votre livre, et ce n’est, mais oui, qu’un très juste dû du plaisir que m’ont procuré, en un temps où la disette des oeuvres d’art s’affirme, vos exquises Petite Épouses.

Je suis chez moi toutes les après-midi jusqu’à quatre heures. Vous êtes donc bien sûr de me trouver dans la lanterne de la rue de Babylone tous les jours de la semaine.

Je suis rentrée avec une âme qui pluviote. Apportez des parapluies spirituels pour vous abriter.

Cordialement votre tout dévoué,

G Huysmans(4)

The first thing that is striking about this letter is its date, 1902, which is relatively early on in Harry’s literary career, her first collection of short stories having been published in 1899. The second thing that is noticeable is Huysmans’ friendly tone, with his open invitation to visit him at No. 60 rue Babylone. Although Huysmans is frequently thought of as an irascible character, it is nevertheless true that he was often generous to other writers, especially those at the beginning of their careers. In her memoirs, Harry says that following this invitation she immediately made her way to Huysmans’ apartment in the rue Babylone, which she describes in some detail, and their friendship blossomed until the older writer’s illness and death intervened.

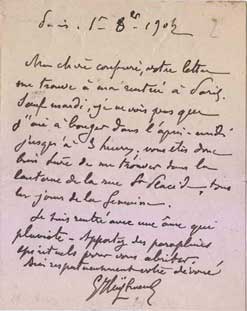

We can now compare the published version with the original letter:(5)

Paris, 1er 8er, 1904

Ma chère confrère, votre lettre me trouve à ma rentrée à Paris. Sauf mardi, je ne vois pas que j’ai à bouger dans l’après-midi jusqu’à 3 heures; vous étés donc bien sûre de me trouver dans la lanterne de la rue St Placide tous les jours de la semaine.

Je suis rentrée avec une âme qui pluviote — apportez des parapluies spirituels pour vous abriter.

Bien respectueusement votre dévoué,

G Huysmans(6)

A number of differences are immediately apparent. In the first instance, there is no address at the top of the letter and it is dated almost two years later, in October 1904. This is important because in March 1904 Huysmans moved from the rue Babylone to the rue St. Placide. Harry has therefore deliberately placed the rue Babylone address at the top of her letter and substituted it in the body of the letter to give the impression that she was a regular visitor to Huysmans from late 1902 onwards. Although it is true that the 1904 date on the letter is somewhat hard to decipher – Huysmans' orthography was sometimes erratic – its date is proved not just by the St Placide address, but also by the reference to having ‘rentrée avec une âme qui pluviote’, Huysmans having just recently returned, in late September, from a trip to Lourdes.(7)

The original is addressed to ‘Ma chère confrère’, which shows that Huysmans knew that Harry was a woman, while the letter in Trois ombres opens ‘Mon cher confrère’. This is because Harry claimed that after receiving her initial letter, Huysmans was under the impression she was a man. It is possible she did this to make her story more dramatic, or maybe to make Huysmans’ initial offer to visit him seem more plausible. (Harry presents Huysmans as a misogynist and claims that he wouldn’t have received her if he’d known she was a woman.) This ‘misunderstanding’, which Harry makes much of, is suspiciously reminiscent of a documented occurrence where Huysmans mistook a female correspondent for a male one. The story is given in Joseph Daoust’s J.-K. Huysmans: Directeur de conscience, lettres inédites.(8) In this instance, Huysmans, after receiving some ‘lettres divines’, had mistakenly assumed their author to be a man, until he later found out she was in fact a woman – Catharina Alberdingk Thijm – who was convinced she had a vocation after reading En route

. In default of any supporting evidence for Harry’s version, it seems more likely that she simply appropriated this anecdote after having heard it from mutual friends, or possibly even directly from Huysmans himself. In any event, not content with deliberately changing the address in the letter she reproduces, it is clear that Harry has fabricated her supposed 1902 letter in Trois ombres from one or more other letters.(9)It is significant that the letter Harry presents as Huysmans’ second letter to her should actually have been written in late 1904. Moreover, the possibility that Huysmans’ first meeting with Harry took place either in late 1903 or early 1904, rather than in 1902 as she claims, is supported by other documentary evidence. Abbé Mugnier was one of Huysmans’ close confidantes during this period, and his Journal, which wasn't published until after Harry's death, refers to numerous conversations he had with him. The first reference that Mugnier makes to Harry in relation to Huysmans is an entry dated 25 April 1904, in which he writes:

Huysmans nous parlait, hier soir, de Myriam Harry qu’il connait. Une Allemande et une Orientale tout ensemble. Elle est née à Jérusalem. Elle a l’horreur de protestantisme, elle est païenne et ne croit qu’à la chair. C’est une allumeuse. Son livre la Conquête de Jérusalem renferme de vraies pages d’art.(10)

The implication of this is that their friendship is of a fairly recent date. Ironically, Harry herself recalls Huysmans telling her that he had talked to Mugnier about her,(11) but while she places this incident early on in their relationship, i.e supposedly between December 1902 and November 1903, we can see from the journal that this conversation actually took place at the end of April 1904. However, there is a more conclusive proof for their friendship having commenced at a later date than the one Harry claims, and that is Huysmans’ own assertion, made in a letter to Léon Leclaire of 12 March 1904, in which he states that his relationship with Harry began ‘il y a déjà des mois, sous le couvert de visite de petite confrère’.(12)

Further proof of Harry’s unreliability, if not her downright mendacity, becomes clear once one starts checking her statements against the factual evidence. Unfortunately, even though the falsity of some of her stories can be proved simply by checking the dates of the incidents she mentions, none of Huysmans’ biographers seem to have done so. Instead, they have reprinted her fabricated version of events unchecked. For example, in various versions of her memoirs, Harry claims that she sent Petites épouses to Huysmans while he was still in Ligugé and that he was under the impression she was a male writer, but that when he returned to Paris he found out she was a woman after having seen a photograph of her dressed in Chinese robes on the cover of a magazine. In Trois ombres Harry goes on to say that when she mentioned the magazine to Huysmans he then pulled it out of the drawer in his desk.(13) However, by looking at the chronology of events one can see that this anecdote is false. In the first place, Pétites épouses was published in April 1902 and Huysmans had returned to Paris from Ligugé in November 1901, so he could not have read the book there or be under any delusion while he was there that she was a man. Conclusive proof that the story is a total fabrication lies in Harry's careless reference to the photograph on the cover of the magazine: although Harry sets the incident in 1902, during what would have been a significant — and surely memorable — first meeting with Huysmans, the picture of Harry dressed in Chinese robes actually appeared on the cover of La Vie heureuse of April 1904.(14)

Having proved that Harry deliberately made false and misleading claims about the chronology of her friendship with Huysmans, I want to turn now to three other contentious assertions that Harry makes in the course of Trois ombres and see how well they stand up to a more rigorous scrutiny. First, the claim that Huysmans travelled to Belgium with the Countess de Galoez, otherwise known as ‘La Sol’; second, that Huysmans considered committing suicide in 1901; and third, her claim to have visited Huysmans just before he died.

As regards Huysmans’ supposed trip to Belgium with La Sol, Harry gives a highly theatrical account of this expedition. She recounts that during the journey, La Sol came to his compartment at night, that 'la tentation était trop forte; ils ne pouvaient plus se contenter d’une platonique amitié…': , and that 'tout sa gâta'. They then separated not wanting to see 'leur rêve ravalé à de basses réalities charnelles.'(15) However, despite Harry’s dramatic recollection of the incident, there is absolutely no evidence that Huysmans travelled in Belgium or Germany with La Sol. Harry is most likely misremembering somethings she has either heard or been told by Huysmans, as in a letter to Cécile Bruyère of 30 July 1899 he says that La Sol went to Bruges in 1897 to solicit help from ‘un affreux prêtre démoniaque que j’ai peint dans Là-Bas, sous le nom de chanoine Docre.’(16). The Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal contains Pierre Lambert’s annotated copy of Harry’s memoirs and his view of this absurd claim is succinctly summed up by the double lines and a question mark inscribed next to the text.(17)

This notion that Harry picked up pieces of information from other people who knew Huysmans and then reused them, often incorrectly, in her own memoirs seems to be echoed in another of Harry’s claims, that Huysmans contemplated suicide in 1901. It is unlikely that, given his views on the subject of suffering and the will of God, Huysmans would have seriously considered suicide at this period, and he gives no hint of such feelings in letters to two of his closest friends, Arij Prins and Léon Leclaire. In the Abbé Mugnier’s Journal, we can see several entries covering the period when Huysmans lived at the rue Monsieur address. Mugnier mentions that Huysmans was unhappy there — mostly because it was so cold — and complained about it at the time, but gives no hint that it was depressing him so much he actually considered suicide.(18) Mugnier does, however, refer to the subject of suicide in a conversation he had with Huysmans in 1892, during which Huysmans said that ‘influences diaboliques’ had urged him to kill himself. Although Mugnier’s Journal itself wasn’t published until many years after Harry’s death, it is perhaps no coincidence that this passage about suicide was published for the first time in René Dumesnil’s La Publication d'En Route (1931), just a year before Harry’s own book came out.(19) Significantly, although several of the claims made in Trois ombres also appeared in earlier versions of Harry’s memoirs, the reference to Huysmans’ thoughts of suicide doesn’t appear in any of the memoirs published prior to the publication od Dumesnil’s book. It is not beyond the bounds of speculation to suggest that Harry inserted these dramatic ‘revelations’ into her book not only to attract attention to it, but also to publicly ally herself with a writer whose reputation was enjoying something of a renaissance at the time. Ironically, a reference to suicide does appear in one of Harry’s ‘memoirs’ of Huysmans published before 1932, the version that appeared under the guise of fiction in Le Tendre Cantique de Siona (1922). However, here it is Siona, the Myriam Harry character, who initiates the subject in the course of a conversation about the difficulties of writing. Siona says to Mirmans (the Huysmans character), 'Il y a des jours où, réellement, j’ai songé à me suicider pour une phrase incomplète,' to which Mirmans replies, 'J’ai connais ça!'. In any event, whether she was refashioning the revelations in Dumesnil’s book or misremembering her own conversations, there is no supporting evidence for her suicide claim, and a considerable weight of evidence to suggest that it was an anecdote she herself fabricated.(20)

The last claim I want to look at here is that involving Harry’s supposed visit to Huysmans just before he died. In Trois ombres, Harry provides a moving account of going to visit Huysmans in early 1907 only months before his death on 12 May. She recalled how thin he seemed, and she congratulated him on having received the légion d’honneur. They talked for a while, but she then had to leave due to the arrival of the doctor, and as Huysmans opened the door for her, he called her by her Christian name for the first time. As she walked down the stairs, she looked back and saw him still standing by the door. Tears sprang into her eyes and with a pounding heart she wished him a loving adieu. This heartfelt scene would indeed be one of the most moving of Huysmans’ life, but for the fact that it is completely fabricated, conjured up some twenty-five years after the writer’s death. If we look at Harry’s account written in 1908, a year after Huysmans’ death, we get a much starker, and much truer picture of events. Harry left Paris for Tunisia sometime after April 1906. She describes visiting Huysmans before she left, and then she says, in her own words, ‘Je ne devais plus le revoir’. She was away for about a year, during which time she says that he sent her a copy of Les Foules de Lourdes and wrote her a letter, dated 5 January 1907. Harry’s 1908 memoir concludes with a statement that she only learned from ‘Madame Bavoil’ that Huysmans was dead the day after his burial.(21) In other words, writing a year after the novelist’s death she makes no reference to having seen him before he died, and indeed explicitly states that the last time she saw him was early in 1906. Harry wrote another article on the third anniversary of Huysmans’ death, published in the Revue des Temps Présent, of 2 April 1910, and yet again, there is no mention of a final visit. Indeed, there is no reference to a ‘last visit’ until after 1927, the year in which Huysmans’ secretary Jean de Caldain died, as he was the only person who could have refuted her story. Although her accounts in the Revue de Paris and Revue des Temps Présent so dramatically contradict the one she gives in Trois ombres, the fabricated memoir has remained unchallenged since its first appearance and has now regrettably passed into literary history.

Taken together these instances of factual innaccuracy, half-truths and out-and-out fabrication, place a large question-mark over Harry’s trustworthiness as a witness to the events of Huysmans’ life. It is to be hope that more letters between the two writers will come to light in the future. It is only by gaining access to the originals of Huysmans’ letters that researchers will be able to map out a factual chronology of his relationship with Harry and begin to correct her numerous errors that have not only gone unchallenged, but have unfortunately worked their way into the official narrative of Huysmans’ life since his death.

Addendum

The sale of Myriam Harry’s archives in 2019 inadvertently revealed another of Harry’s misrepresentations, further undermining her credibility as a witness. In Trois Ombres (pp. 33-34), Harry describes how, as she is leaving Huysmans’ study after what she claimed was her first visit, she noticed a pile of new books, copies of the recently-published De Tout. Huysmans took one and dedicated it to her with the inscription A madame Myrrhiam Harry, respectueusement son dévoué, G. Huÿsmans. But while Harry’s archives did include four copies of books that carried inscriptions from Huysmans to Harry, De Tout was not one of them. Harry’s copy of De Tout (as well as a 1903 copy of L’Oblat) was actually signed to Georges Vanor (1865-1906), the symbolist poet with whom Harry had had an affair in 1897 and who was most likely the man who facilitated her meeting with Huysmans. Once again, another piece of Harry’s ‘evidence’ that she visited Huysmans before 1903 (De Tout being published late in 1902) turns out to have no substance, and reveals a deliberate attempt to falsify the facts.

NOTES

(1) Fonds Lambert 48.

(2) Information on Faouaz Perrault-Harry (Chombard-Gaudin gives his birth name as Faouaz Qabalân al Hatim, though an internet search returns no results on that name) is equally scarce. Evidence from letters and photographs would suggest that he was about ten years old when the Perrault-Harrys were first introduced to him, probably some time around 1926. He was apparently still alive in 2005 when Cécile Chombard-Gaudin wrote her initial biography of Harry, which would have put him in his nineties at the time. But he must have died sometime after that, though there is no information about his death in the second edition of Chombard-Gaudin’s book of 2019. Harry’s archives were sold at auction in 2019, presumably after the death of Perrault-Harry’s partner.

(3) Email from Cécile Chombard-Gaudin to author, 1 June 2006. Chombard-Gaudin’s recent biography, L’Orient dévoilé: Sur les traces de Myriam Harry (Turquoise, 2019) offers a slightly revised account of the friendship between Huysmans and Harry than that contained in her original version of Harry’s life, Une orientale à Paris: Voyages littéraires de Myriam Harry (Maisonneuve et Larose, 2005). However, Chombard-Gaudin still relies far too heavily on Harry’s own unsupported version of events as recounted in Trois ombres, despite the existence of Huysmans’ 1904 letter and the internal evidence that disproves Harry’s chronology. It is to be hoped that a later edition will incorporate this documentary evidence and give a more nuanced and factually accurate account.

(4) Myriam Harry, Trois ombres (Flammarion, 1932), p. 19.

(5) The letter was originally sold in a Christie’s auction of ‘Important mobilier et objets d’art: Flammarion’ in 2003. Presumably the letter was acquired or came into Ernest Flammarion’s possession around the time of the publication of Trois Ombres, which his firm published in 1932.

(6) Manuscript copy in possession of the author. In the preface to L’Orient dévoilé, Cécile Chombard-Gaudin states that Harry’s adopted son, Françoise Perrault-Harry, destroyed Harry’s literary archive before his death, which may mean that the originals of Huysmans’ letters to Harry will now never come to light. The single letter printed here which escaped this destruction clearly reveals Harry’s willingness to publish fabricated ‘evidence’ in order to boost her own literary reputation. While he was alive, Perrault-Harry consistently refused to allow anyone access to Harry’s archives, and this may have been to stifle evidence of her intellectual dishonesty. It isn’t exactly clear how this 1904 letter came to separated from the rest of the Harry archive – it is possible that Harry gave it to Flammarion as a memento of Huysmans, but this is just speculation. Despite Chombard-Gaudin’s reference to the destruction of the archive, at least some of it appeared in an auction sale in Paris early in 2019, so it may have been a selective process. Interestingly, a Huysmans-related lot appeared in the sale, consisting of four books dedicated to Harry by Huysmans. The two original editions – Trois primitifs and Les Foules de Lourdes – date from 1905 and 1906 respectively, while the other two, La Cathédrale and En rade are from later editions – the former was a 25th edition from 1904. Harry did possess an original signed copy of De Tout (which also appears in the auction sale), but it was dedicated to Georges Vanor, who she had an affair with and who was most likely the man who facilitated her meeting with Huysmans.

(7) Ghislain de Diesbach (ed.), Journal de l’abbé Mugnier, 1879-1939 (Mercure de France, 1985), p.149.

(8) Joseph Daoust, J.-K. Huysmans: Directeur de conscience, lettres inédites à C. Alberdingk Thijm (Durand et Fils, 1953), p. 7.

(9) The suspicion that Harry fabricated the published versions of her letters becomes almost a certainty after seeing another lot in the Harry archives auction sale mentioned above. This consists of three partial ‘transcriptions’ of letters from Huysmans in Harry’s handwriting, though as the originals have never surfaced it is more than likely that these are simply fabrications. The fragments have some similarities with versions published in Trois ombres, but there are clear differences, showing that Harry has invented or fabricated large portions of the letters she published.

(10) Ghislain de Diesbach (ed.), p.146.

(11) (Trois ombres, p. 51)

(12) Huysmans to Léon Leclaire. Fonds Lambert 60.

(13) Myriam Harry, ‘En Mémoire de J.-K. Huysmans’, Revue de Paris, 15 May 1908; Trois ombres, p. 23-24.

(14) Harry also recounts an anecdote during this period which she claims took place in 1903. She recalls Huysmans proffering an unflattering comment about Charles Deremme, who had just sent Huysmans his latest book of poems, La Tempête. However, the book wasn’t published until 1906.

(15) Trois ombres, pp. 67-8.

(16) René Rancoeur, Correspondance de J.-K. Huysmans avec Madame Cécile Bruyère, Abbesse de Sainte-Cécile de Solesmes (Paris: La Pensée Catholique 13, 1950), p. 22.

(17) Copy of Trois ombres in Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal.

(18) Ghislain de Diesbach (ed.). See entries for 8 and 23 May 1902 (p.132), for example, where Huysmans admitted that he felt ‘déprimé’, and told Mugnier that he ‘veut quitter son apartment’.

(19) Réné Dumesnil, La Publication d’En Route (Société Française d’Editions Littéraires et Techniques, 1931), p. 88; Ghislain de Diesbach (ed.), p. 76.

(20) In an article published in Candide in 1932, Harry again imputed thoughts of suicide to one of her biographical subjects: Anatole France. She reported France’s wife and former mistress, Emma Laprévotte, saying: “Oh ! vous ne sauriez croire combien nous étions malheureux, désemparés, abandonnés de tout le monde. M. France, sans amis, sans bibelors, sans livres, accusé de toutes sortes de forfaits, a sérieusement songé, je vous assuré, au suicide...” It is probably no coincidence that Laprévotte, the only person who could have proved or disproved Harry’s story, had died two years previously in 1930.

(21) Harry betrays herself again here in that Julie Thibault, the model for Madame Bavoil, had left Huysmans’ service in 1899, years before Harry’s first visit to the writer. Anyone who knew Huysmans well would have known that his housekeeper up until the time of his death was not the Madame Bavoil of his novels.

Bibliography

Dumesnil, René. La publication d'En Route de J.-K. Huysmans. Societé Française d'Editions Littéraires et Techniques, 1931.

Harry, Myriam. Revue de Paris, 15 May 1908.

Harry, Myriam. Revue de Temps Présent, 2 April 1910.

Harry, Myriam. Le Tendre Cantique de Siona, Fayard, 1922.

Harry, Myriam. Trois ombres, Flammarion, 1932.

Mugnier, Abbé. Journal 1879-1935, Mercure de France (1985).

Rancoeur, René. Correspondance de J.-K. Huysmans avec Madame Cécile Bruyère, Abbesse de Sainte-Cécile de Solesmes. Paris: La Pensée Catholique 13, 1950.

© 2006 (original article revised in 2022 to include new information and details).